NOWHERE NEW YORK: AN INTERVIEW WITH JULIA GORTON

NOWHERE NEW YORK: AN INTERVIEW WITH JULIA GORTON

(Front cover to Julia Gorton’s upcoming book Nowhere New York: Dark, Insulting + Unmelodic.)

(Teenage Jesus and The Jerks feat. James Chance live at Max’s Kansas City. Photo by Julia Gorton.)

Julia Gorton is having a little bit of a moment. And a well-deserved one at that. In fact, it’s been a long time coming. After having spent many years away from the world of photography that first gained her entry into the underground arts and music scenes in New York City in the late-1970s— with a particular affinity for the punk and No Wave crowds inhabiting places like CBGB, Max’s Kansas City, Hurrah and Tier 3, among other subterranean draws— over the course of the past half decade she has slowly reemerged in the public eye, thanks to the rise of social media, to reclaim iconic images from her impressive archive from the largely lawless world of internet poaching on sites like Instagram and Twitter. Having noticed her images being used without credit or permission on countless accounts that weren’t her own back in 2015, she finally took it upon herself to not just regain ownership over her work in the digital realm, but to also reintroduce herself to a modern media landscape that had dramatically shifted since her earliest days as a freelance photographer working for publications like New York Rocker and The Village Voice.

Originally from Wilmington, Delaware, Gorton first arrived in the city in 1976 to attend college at Parsons School of Design as a wide-eyed creative ready to take on the mythic metropolis during time off from her studies, and ended up— almost by chance— as one of the premier documentarians of some of the most legendary and incendiary cultural movements the Big Apple had ever given birth to. Having been hipped to some of the revolutionary music coming out of the Downtown clubs on the Lower East Side by her then-boyfriend and fellow artistic traveler/Wimington native Rick Brown, Gorton picked up a Polaroid camera upon her arrival in the city and began in earnest to photograph some of the original trailblazers from punk’s first wave through groups like Blondie, Televison and Talking Heads, followed soon after by an immersive look at the often brutally atonal, willfully abstract, lyrically dark, and gleefully confrontational No Wave scene that had coalesced around acts like Lydia Lunch, The Contortions, Mars, DNA, and a host of lesser known, yet equally vital, groups that were challenging not just the musical foundations and hierarchy of rock and roll, but the entire aesthetic premise of music itself. Drawing inspiration from experimental composers, avant-garde jazz, world music, funk, punk, and anything else they could grind into their heady mix, the No Wave acts that burned fast and bright throughout the end of the decade, which Gorton so expertly captured in stark black and white images as she graduated from Polaroids to a traditional film camera, would go on to take an unusually fabled place in the pantheon of modern music for a scene that few heard or witnessed in person, let alone on record.

Which is one of the very reasons her photographs from the era have taken on even greater import as a window into a scene that, despite its intense yet short lifespan, has continued to exhibit a remarkable influence on contemporary sounds in a way that belies its initial historical footprint. Having expanded beyond the small slew of bands that inhabited the original scene, several of whom were selectively documented on the seminal No New York compilation produced by Brian Eno in 1978, to later include more dance-oriented groups like Liquid Liquid, Konk, and Defunkt, alongside groundbreaking female-centric acts like Lizzy Mercier Descloux, ESG, Bush Tetras, Y Pants, Ut, and The Bloods, the bands that made up the first few iterations of No Wave would go on to inspire everyone from early Sonic Youth and the Swans, to LCD Soundystem, Liars, and the Yeah Yeah Yeahs, just to name a few. And that was just in New York alone. Revolving around a robust and committed interdisciplinary DIY ethos that threaded together transgressive art, film, photography, and publishing— with music as the tie that bound it all together— despite having set out to destroy cultural hegemony and in many ways kill their own idols, it also left a lasting impact that not only built on historical antecedents, but ended up depositing building blocks of its own for generations yet to come. Often touted as a reflection of the dilapidated state of the City That Never Sleeps, and late-70s anti-disco burnout (despite dabbling in mutant disco themselves), the No Wave scene’s dim and uncompromising attitude was one that set a high bar for anti-art and music, leaving behind both burning cinders and a remarkably long legacy in its wake.

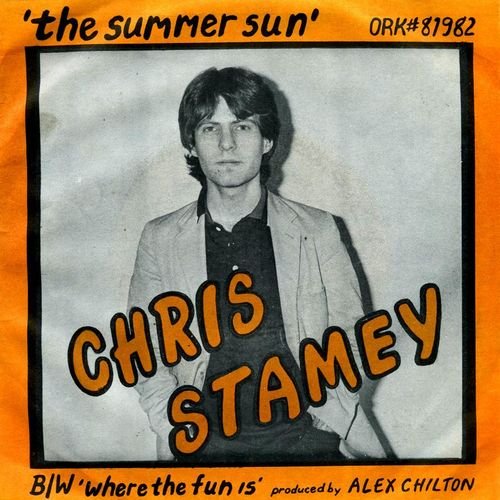

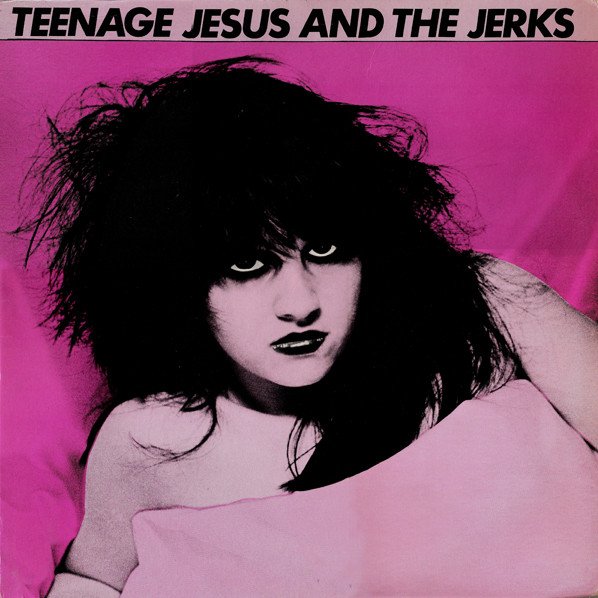

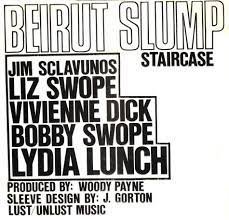

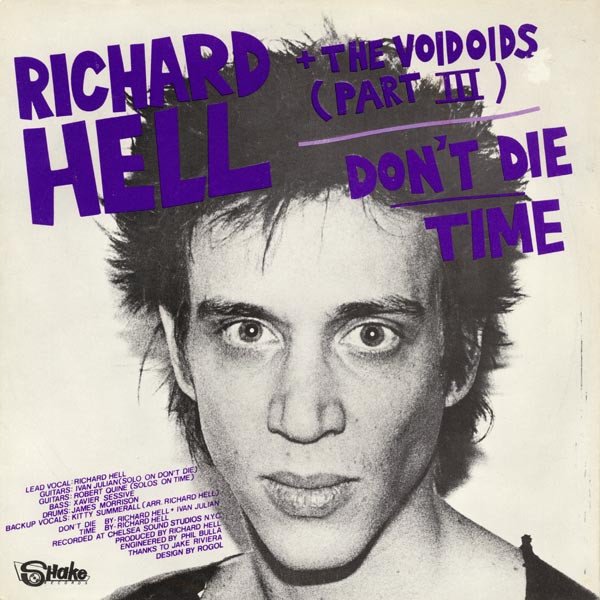

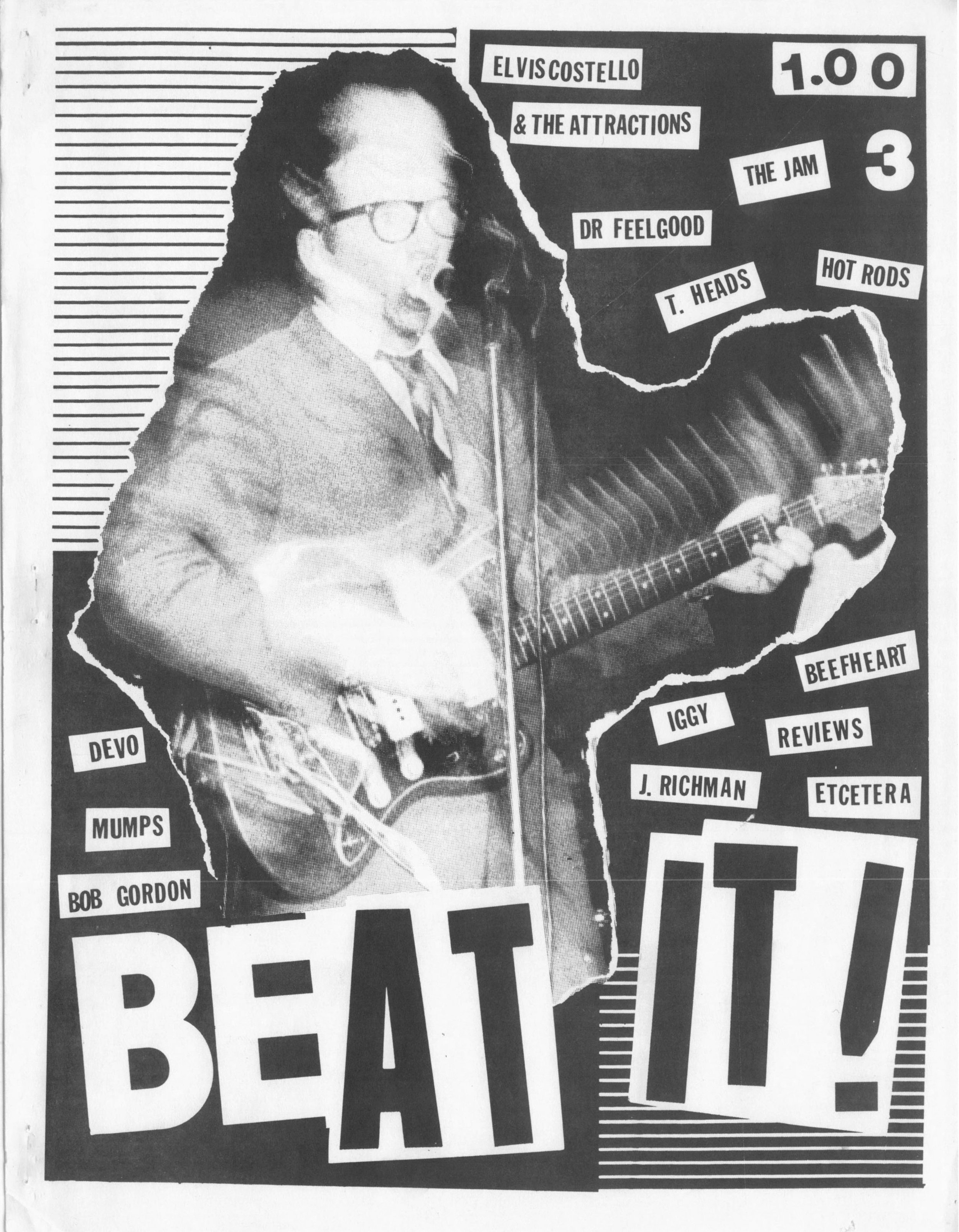

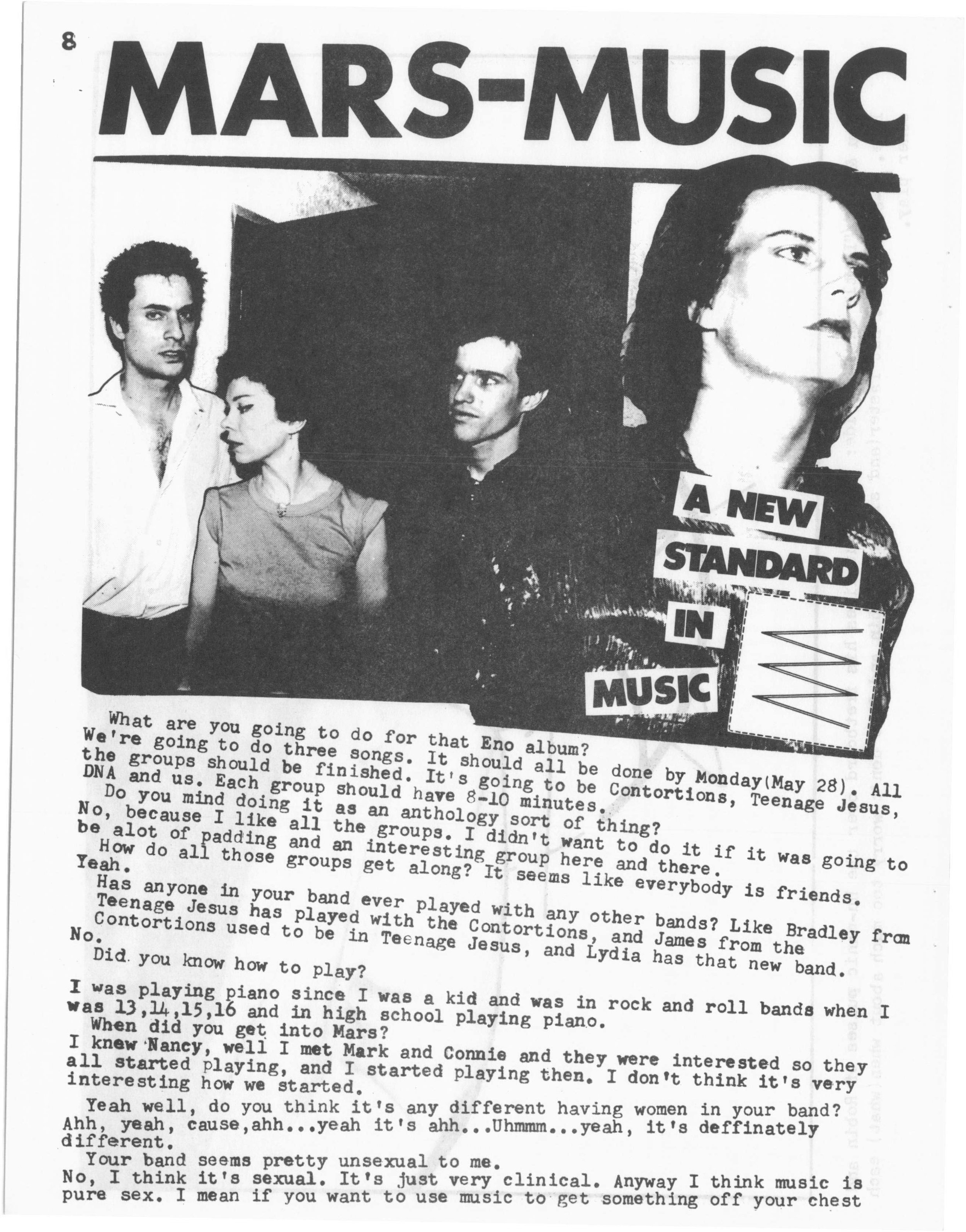

Having been front and center for that initial sonic explosion, Gorton not only documented many of the acts and assorted scenemakers that made it exciting and viable, she also helped proselytize for it through the DIY fanzine she co-started in1977 with Brown called Beat It!, which not only provided early exposure and press for many of the local bands of the time, but also acts from around the country and world who were playing New York City at the time, making a meaningful contribution to the historical record of the era. As an adjacent pursuit in line with the degree she was pursuing in school, she would also have her work featured on contemporary record covers for notable labels like Ork, Lust/Unlust Music, and ZE, having her name, photos and design layouts featured on albums, EPs and singles by artists like Richard Hell and The Voidoids, Chris Stamey of The dB’s, Teenage Jesus and The Jerks, Beirut Slump, and James White and The Blacks. For his part, Brown— who not only helped publish Beat It!, but was an active member of the No Wave community himself through bands like Information and Blinding Headache— would go on to become a permanent fixture on the Downtown scene through acts like Curlew, V-Effect and Fish & Roses, and into today through his celebrated and droning new music ensemble, 75 Dollar Bill. But whereas Brown would continue to actively participate in New York’s underground audio explorations for the rest of his adult life, Gorton took a different, more career-oriented tack by leaving the music and photography world behind starting in the early-1980s, as she graduated from Parsons and began to pursue a life of professional design work at places like National Lampoon and Condé Nast, followed by a more quiet domestic lifestyle with the arrival of her first child in 1986. Continuing to do freelance art and design, including on children’s books, Gorton would eventually find her way back to Parsons as a teacher and program director, before leaving in 2020 to retire. Having become increasingly bugged by a sense of unfinished business with regards to her love of photography and the little known legacy she had left behind over thirty years earlier, starting in 2012 she began taking photographs again and posting them on Tumblr, which subsequently lead her to start to explore her back catalog from the late-70s, particularly as photography-based social media apps like Instagram began to rise to the fore. Seeing an opportunity to rebrand herself after noticing peers like David Godlis utilizing spaces like Instagram to get his work and name out to the public, and hopefully new and younger audiences, she seized upon the new technology to create what has now become a nearly 27,000 follower-strong account in 2016, with reach all across the globe, highlighting an incredible body of work that has remained largely outside of the greater public’s view for nearly four decades. An impressive and eye-opening look at not just the punk and No Wave scenes, but really New York as a whole and some of the wild and crazy characters who inhabited its streets and clubs during the tail end of one of its most dynamic decades, it has quickly become one of the go-to accounts for anyone interested in obscure music history and the images that go along with it.

(Record sleeve designs + photos by Julia Gorton, l-r: Chris Stamey’s “The Summer Sun”/”Where The Fun Is” single on Ork Records, 1977; Teenage Jesus and The Jerks compilation on Migraine Records, 1979; back cover to the Bobby Berkowitz/Beirut Slump split 7” for “Try Me”/”Staircase” on Migraine Records, 1979; Richard Hell and The Voidoids/Neon Boys split 7” for “Don’t Die” +”Time”/”That’s All I Know (Right Now)”+”Love Comes In Spurts” on Shake Records, 1980.)

Having gotten the attention of curators from museums and other arts-oriented groups from around the country and world who were interested in reinvestigating and celebrating her creative output, what started out as a way to reclaim a past life, quickly morphed into being included in exhibits at the Museum of Modern Art, the Museum for the City of New York and the Museum of Art and Design, having her work shown at the International Center for Photography, and a residency at the Doomed Gallery in London, to name just a few. It was also around that same time that Felicia Gail, then curator at the Pensacola Museum of Art, contacted her about showing some of her photographs in Florida, which would ultimately lead to a newfound and fruitful relationship with the coastal city, and would find her not only doing a joint exhibition at the museum in 2018, but also being asked to return to to do a week-long residency at the 309 Punk Project house there in late summer of 2022. As a recently formed non-profit organization centered around what is believed to be the “oldest continuously inhabited Punk House in the south,” the group, which is run by an all-volunteer collective, has made it its mission to not only preserve punk history from around Pensacola and the Southeast, but to help bring aesthetically-aligned artists and musicians from around the country to present a variety of programs to local audiences about the larger diaspora of DIY culture in all of its various forms. Jumping at the opportunity, Gorton would return to the gulf community to not only exhibit more of her photographs, but also do a series of free portraits with natives and traveling visitors, providing a unique experience for anyone interested in the continuation and legacy of underground music photography from one of the women who helped capture its essence so many years ago.

But that’s just part of the story. Having been putting together a comprehensive book of her punk and No Wave photographs over the past eight years— appropriately titled Nowhere New York: Dark, Insulting + Unmelodic— which she is set to self-publish at the end of 2022, Gorton’s life in many ways has come full circle back to her own DIY roots and the old days of Beat It!, finding inspiration from the people, places, music and vibe that she so intimately captured in her youth while attending Parsons. A stunning insider’s look at a series of subcultural moments that will never exist again, the book is both a tribute to the music and musicians of the era, as well as a remembrance of an entire community made up of fans, onlookers, promoters, venues and DJs, that helped make the overlapping movement what it was. Filled with essays from people who were there and contributed in some meaningful way to the scene’s vitality, including an introduction by Lydia Lunch and pieces by Thurston Moore and Lucy Sante, all of which provide insightful and sometimes contradictory perspectives on how it all went down, the book also offers up an assortment of related ephemera— from posters and guest lists to album covers— bringing into sharp focus all of the many facets that created the vibrant if menacing scene we now read about in history books and magazines today. And she was there to capture it all in all of its gritty, grimy glory. It’s a remarkable story, and one that proves that everything that’s old can always be new again, especially when recontextualized for a modern audience.

I had the opportunity to sit down with Gorton following one of her marathon portrait sessions during her residency in Pensacola last month, to find out a little bit more about not just the book project and her return to photography, but also talk about broader issues about artistic influences, how history is made and told, who tells it, and how it sometimes gets muddled, misrepresented and misperceived along the way. Particularly as it pertains to the No Wave scene.

This is our conversation.

________________________________________________________________________________________

(Scenes from Julia Gorton’s residency at 309 Punk Project in Pensacola, FL. Photos by Lee Shook.)

AV: So I just wanted to ask you to start off with about how you got involved with the 309 Punk Project and about your residency here in Pensacola.

Julia Gorton: I met everyone at 309 through Felicia Gail who was working as a curator for the Pensacola Museum of Art. This was probably about, I'd say four or five years ago. And, at some point previous to that, I had started building up my Instagram account to try to create a connection between my name and my work, ‘cause work was out there and people didn't know I'd done it. I'd been building it up and there'd been some press and somehow Felicia found me on Instagram and thought I would be a good addition to this show that she was putting together that had Jimbo Easter, who was an artist and performance artist from Detroit, and Matty Jankowski who was a local local artist who's since passed. And so, I was in my class and teaching, and I was on break and I got this call from her. And she just called me and was like, “Hello, this is Felicia.” And so she invited me down and it was at a point when I really felt like I needed to get out and do some things related to this body of work. And we came down and we had— I came down with my husband— and we just had a great time with everybody. And the show was good. Show was really wonderful. And we met Scotty [Scott Satterwhite; Co-Volunteer Collaborative Executive Director at the 309 Punk Project] and we met Val [Valerie George; Co-Volunteer Collaborative Executive Director at the 309 Punk Project] through Felicia. And so, I stayed in contact with that whole crew through social media ever since then.

AV: Was this your first time to come to Florida or the Deep South? Had you spent much time in this area at all before?

Julia Gorton: No, no, no. I mean, I've been to Miami and Tampa, St. Pete, Sanibel. At that point I'd say it was probably— it felt more South than any other place we'd been. I don't know what that even means from a New York/New Jersey perspective, but it was just really interesting because they all whisked us away to this amazing bar where there was like smoking, or more smoking than I've ever seen or smelled in my life. There was so much smoke. And then there was just the best karaoke I've ever heard. So, you know, my husband and I, we had this great time and we're like, “We have to get back there. How are we gonna get back?” Like, we have to get back to that feeling. And then COVID hit and this place started to explore the idea of residencies and Valerie reached out and said, “We want you to come down,” and I'm like, “I want to come!” So here I am.

AV: Excellent. Well, to switch gears a little bit here, you were born in Delaware but have been a lifelong New Yorker— or New Jersey and New York— since 1976, and I was gonna ask you what first drew you to the city as a young person, and just how much of your interest in the city was through music and art and photography?

Julia Gorton: I think a lot of people are drawn to New York, and there are groups of kids at high schools throughout probably the whole country that just feel like the place that they've grown up in is not satisfying or is not a good fit for them. And so you get this idea that you're gonna leave or go to college or something. And I started thinking about it, you know, really, probably quite young. And there were different kinds of things that you would see, like you watch TV and you see there's New York and big buildings and there's a doorman, and people have jobs— creative jobs. So my dad was a chemical engineer, which is a creative occupation of a sort, but I didn't know any artists or designers or photographers growing up. So, with the support of the teachers I had, they directed me towards a couple of schools in New York, and I was like, ‘This is it. I'm getting outta here.’

AV: Did you know much about what was happening in the music and art scenes at the time when you first got there?

Julia Gorton: Well, by the time I got to New York, I did more because I had a boyfriend in Delaware who was a year older than me. And so he went up to NYU the previous year and he started writing to me about CBGB.

AV: This is Rick Brown?

Julia Gorton: Yeah, Rick Brown. And what I liked that he did is he would go to the galleries and he would get like the gallery invitations— I wish I had them— and they were all marked with the bulk mail symbol on the back. So he would hijack their bulk mail and he would then write me letters and notes on gallery cards and just drop it in the box. And so, I knew there was stuff going on and he was very musical and introduced me to that. You know, I liked Rod Stewart and Elton John and Chicago, maybe because my brother liked it. And then I met Rick and Rick's dad was a jazz drummer. And so Rick had like jazz records and LA folk music, and we listened to stuff like Wild Man Fischer, some Jonathan Richman. And I think when I was in high school the Patti Smith record came out, and so I was starting to get some of those albums into my collection. And so I knew when I got to New York, he already knew all the good places to go, and then he introduced me to those places. So, a debt of gratitude to Rick Brown.

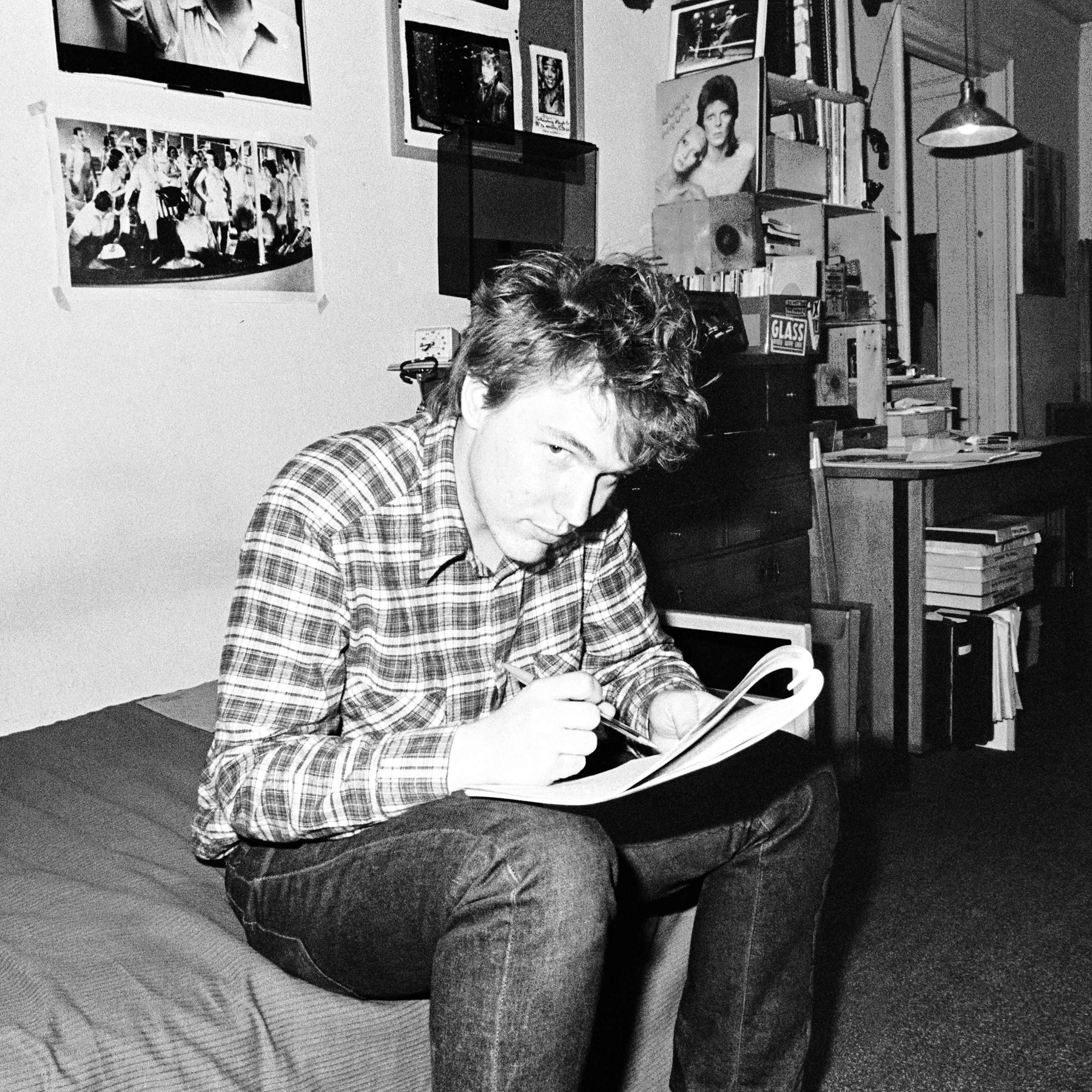

(Rick Brown in Julia Gorton’s college dorm room working on Beat It!, 1977.)

AV: Well, I was actually gonna ask you about the importance of your relationship with each other. A lot of people may know Rick's work from 75 Dollar Bill now.

Julia Gorton: Apparently, and this is so interesting, because somebody was here at the opening and I was showing her something and I was like “Oh yeah, that's my old boyfriend, Rick Brown.” She goes, “Rick Brown!?!” I'm like, “Yeah. He's in this band now called 75 Dollar Bill.” She goes, “75 Dollar Bill! I know!” And so I thought, he’s been a musician forever and his dad was a jazz drummer.

AV: Well, people may also know him from Curlew and V-Effect and some other Downtown bands.

Julia Gorton: Yeah. But it's sort of interesting because he's been in tons of different bands. When we were in college we were both in the NYU dorm, the Brittany, on 10th and Broadway. And so he and Willie Klein, who was in Mofungo, and I and Kymberly Bond, who was in Blinding Headache and Mofungo, and Dave Sutter who— I mean, a bunch of people would get together and we would go down into the basement in the room next to the washing machines and we would like jam. And one of them had like a big piece of like curbside-find trash metal that they would just pick up and drop. And they'd be like, “Krrrang!!!” So, the name Blinding Headache was, I thought, really funny. But they were kind of noisy, and so he's worked at it for years and years and been in many different bands. But the recent one seems like it's really caught on. They're great.

AV: Yeah, they played at Big Ears Festival in Knoxville recently. I saw them there, which was fantastic.

Julia Gorton: Yeah, he’s got his crate and the whole thing.

AV: And you all started Beat It! together. I wonder if you could talk a little bit about that for people who may not know what Beat It! was and sort of what you were trying to document in New York City, but also bands that weren't from New York City.

Julia Gorton: Yeah, so Rick and I ended up in the same dorm and saw each other a lot. He was at NYU and I was at Parsons, and I think that I was taking a lot of photographs, and he is just such a fan, and very knowledgeable about whatever was happening across multiple scenes at the same time. And I think, being a design student, I was interested in all the different kinds of tabloids and scenes and I worked for New York Rocker. But we thought, ‘Oh, we could do something.’ We could do something like Mark Perry from Sniffin’ Glue from the English scene. We're like, ‘We could do this, let's do this!’ And so we just started putting it together. And so the first volume of it was primarily photographs and captions. And I think Rick then started writing more and more, and I did some interviewing with a number of different people. And I was the transcriber and the typer and the designer and the photographer. And I brought in Robert Sietsema, who now is a writer for Eater and is a fabulous photographer. And we just plowed through it. It was kind of fun. You know, like we could make something and somebody would buy it. Like, ‘Oh my god, they bought it! It sold out. What?’…super exciting. And then we met Chris Nelson and Phil Dray from NO magazine, so sort of the ‘zines brought us all together, and then they ended up in bands together.

AV: Well, there was this great DIY culture that was happening. It was about movie-making, ‘zines, photography— and of course the music was a big part of it. But it was a lot of interdisciplinary things happening all at once. I was wondering if you could talk about that and just how dynamic that was amongst— it seemed like— the crowd that you were running with and documented.

Julia Gorton: I mean there really wasn't anybody to help you do anything. And there wasn't any way to figure out how to do something. You just kind of had to want to do it and then try to figure out how to do it. Like the first copy of Beat It!, if you look at it, is all single-sided copies because I didn't know about double-sided copies. I was like, ‘What? You can print on both sides of the paper? This is unbelievable!’ I knew it happened in magazines and stuff but I didn't know how to do it. And so, you know, you couldn't just look up ‘how do you make a ‘zine.’ And you just kind of had to see what other people were doing, so that kind of DIY crowd was coming from England and California and you would see stuff in stores or at friends' apartments, then you would learn about people that were interested in the same thing. Now, you mentioned films, because I'm always interested in how many scenes were kind of happening at the same time and how they were really closely related, but they didn't always overlap. So, a lot of people in film, I didn't know at all then. They had gone to film school, or they— I just didn't know them. I knew the music people, and I knew some of the photographers.

(Selections from Beat It! fanzine, created and published by Julia Gorton and Rick Brown. Images courtesy of Julia Gorton.)

AV: It's interesting to think about the interdisciplinary stuff, and just the crossover of musical ideas that were happening at the time that you got to document so much of with No Wave. You know, in one sense it's this kind of brutal music, but also there was a lot of jazz and funk and world music that was happening in there as well. So there was a sort of interdisciplinary aspect there too, and I think about you as a designer turned photographer turned ‘zine person. It just seemed like that was happening on micro-levels as well as macro-levels.

Julia Gorton: Yeah. I wonder— I didn't keep a diary, so trying to sort out and piece together my life based on the images that I have in my archive— like, how quickly did this happen? How/when did I go from Polaroids to actually shooting film in New York? And, you know, I can sort of cross-reference the images and get an idea by looking up when this gig was at this place. And so, how quickly things changed, because you mentioned world music and I feel like, where did that sort of come in? Because I think by that time, it seemed like things really had shifted away from this scene, except it was embedded in some of the jazz and experimental musicians from their work. Like I say about Rick, he was always listening to Gato Barbieri and lots of different kinds of music and different kinds of jazz. And so, when I go back now and listen to that music, I'm like, ‘this is full of Stockhausen, and this is a little like Ornette Coleman here, and this is a little bit like….,’ you can hear that avant-garde thread coming through the No Wave sound.

AV: A lot of mishmash of ideas happening.

Julia Gorton: I mean, is it a surprise that I make collages? It's like, put it all together. But I was gonna say that, at the time, I was a student and I took this class called “Appreciating Modern Music.” So it was about classical modern music that was 12-tone and other stuff. And I remember the preface to the class was something like, “you may find this music very hard to listen to, it’s very atonal and a lot of people find it very dissonant.” And so, you know, I'd go up to like Lincoln Center and check out the records that I was supposed to listen to for class and bring them back to the dorm and listen to them. And I thought, I don't know what they're talking about. This stuff is really, really pretty. It's beautiful. It's atonal? Like dissonant? I still don't hear it that way, because I'd heard Lydia Lunch and James Chance.

AV: I was gonna ask you about some of those figures that you got to document and work with like Lydia, who I know you did a lot of work with. But you know, you had this backdrop that’s talked about a lot with the No Wave scene of the ‘city in decay,’ and that the music reflected that, and I was wondering if you could sort of set that scene a little bit for us, and maybe how Lydia's atonal approach to guitar, or James' sort of brutal, confrontational performances reflected that, if you can reflect on it yourself.

Julia Gorton: You know, it's interesting, people have asked me to try to describe what it was like, and I think it was just so exciting to be in New York from Delaware. It was like, ‘Oh my god, there are stores and I can walk past them. And there are cars and there are subways and there's coffee carts and there are people.’ [laughs] And I mean, it was just so different than suburban life. So I think that sometimes I see the pictures of then and I think, ‘god, it was just really decrepit.’ You know, my husband and I talk about how it had such a foothold in almost like another century. And so you would see these remnants— and we lived in the East Village, which was full of Ukrainian and Polish immigrants that were probably my age that I am now— and they just seemed so old, and so like, who are they? We just didn't really understand the history of the city. We just wanted to be there. And there was— I mean, it was amazing— there were these areas where there were like tons of used bookstores and tons of used records. There were categories of neighborhoods, and so it was super exciting to explore that. And I think you just sort of missed— you know, you just kind of didn't pay so much attention to the things that were like, you watched where you were stepping ‘cause there was dog crap all over the place. But it was just part of the streetscape.

AV: So you had a little bit of blinders on because of just being young and in the city.

Julia Gorton: Yeah. And so, I think that the thing about Lydia is like, I had never seen anybody like her in my life. And I hadn’t seen anybody that looked like her, that talked like her, that acted like her, that sang and screamed like her. It was like whiplash.

AV: Was that jarring coming from Delaware?

Julia Gorton: I mean, I knew some odd people in Delaware, but she was very exciting. And she's very nice to work with, so it's also funny to think, well, what was our relation really like? What did we talk about and how chatty were we? And was there a lot of like, “Hey, how ya doing?” I just don't really quite remember. And I saw her not that long ago and it just all came back to me like, ‘oh, I remember her persona.’

(Lydia Lunch poses for a photograph in her apartment, 1979. Photo by Julia Gorton.)

AV: Did you have any favorite acts from that era that particularly drew your interest or caught your eye either from a photographic standpoint or from a musical standpoint?

Julia Gorton: Well, I think one thing about the music scene back then, there was a lot going on. So you might see somebody like Robert Gordon with Link Wray, and then you might see some band like the dB’s or Alex Chilton. And you might see some bands like the Dictators— they were very specific. They were great. I loved them. And then you would see Lydia and Mars and Information. And so, that was all during a week and you didn't have to choose, like, ‘I like the Dictators, so I'm not gonna like Information.’ It all fit together. So, I loved Mars. And I loved Information. And I listen to the music and it— I don't listen to it all the time, or hardly at all— but when I listen to it I still find it bracing and exhilarating.

AV: Well again, there's sort of a tearing down of boundaries— musical boundaries— and you all were experiencing it as listeners and as documentarians absorbing all of these things, all of these influences, and just being part of that dynamic period. I've always been fascinated by it as just an era where people were trying out new things.

Julia Gorton: You know, it's funny because I think as much as we think we're trying out new things, we're building on a base of all those other things that we've heard and seen. So, you know, people have asked me to talk about why my work looks the way it does. And there are a lot of reasons why, I can see now, it looks the way it does. And it has to do with time and place, your personal interests. Like you really like people, you like the way people look, it's exciting to see people looking different.

AV: They're stylized as human beings.

Julia Gorton: Yeah. It's like, ‘wow, look at that.’ And also, then the lighting and the contrast comes from kind of your limitations with you can't do like a zone system photograph, or whatever it was called, by Ansel Adams. Like, you don't know how to get great tones. I didn't know how to do that. And I didn't particularly like them, but I couldn't have done that technically at all. I got my film developed— it looked thin or it wasn't thin— and then I tried to make it look sort of somewhat consistent with graded paper. But, you know, years later looking back, you're like, ‘oh, I just copied a horror film here, and here I copied like a Lana Turner cheesecake picture.’ Like this picture here, what is this? [points to photo of Anya Phillips] Who is this? Why does she look like this? She looks— in a way it's very glamorized based on like a George Hurrell photo or something. So, you know, things being fresh and new, I think it might be fresh and new to the people who can't quite understand what the influences are. I remember one time, like in high school, platform shoes just came out. I'm like, “I have to have these platform shoes. They're amazing, mom.” And she goes, “Oh yeah, we had those before.” I said, “No, you didn’t.” I couldn't believe that they weren't new.

AV: Everything old is new again.

Julia Gorton: Right. I know. But I was like, “No, no, no, these are new. You didn't have these, we have these.” [laughs] But, it's all based on…

AV: There are building blocks from the past.

Julia Gorton: There are building blocks from the past, yeah.

(Lydia Lunch, Adele Bertei and Anya Phillips at CBGB’s, 1978. Photo by Julia Gorton.)

AV: Well, speaking of Anya Phillips, there was a strong female presence, particularly in the No Wave scene, and in the punk scene too with Patti Smith and Debbie Harry and Tina Weymouth from Talking Heads. But it seemed like in the No Wave scene there was a very robust female presence in the bands, with you as a photographer, Anya Phillips was someone who was a scenemaker and manager, and I wonder if you could talk about that and just how much females contributed to the No Wave scene, either on musical front or just in helping to foster the creative community around it.

Julia Gorton: You know, I honestly was not even aware of that until Byron Coley interviewed me for the book that he did with Thurston Moore [2008’s No Wave : Post-Punk. Underground. New York 1976-1980]. And he's like, “Oh, you know”— I don't know how he phrased it— but it was in a very sort of academic, kind of looking back way, that talked about the women being so integrated well. And I think I felt— I was sort of surprised when he asked me this. ‘Cause I'm like, “I don't know. I never really noticed that we were.” I think we just were integrated well. And so it wasn't like there was anybody holding anybody back or making decisions about who could play or not play or photograph or publish. It was just— it felt well-balanced and relatively healthy that way.

AV: I feel like, again, boundaries were coming down and so the people were having half-male/half-female bands, all-female bands. Y Pants and Ut— you know, all these great female-centric outfits.

Julia Gorton: Yeah, I think if the music was good and the performances were good, it was just everybody was happy to see what people were doing. Bill Arning, who was in Student Teachers, wrote something for my book, and he was talking about how at a certain point the crowd did change. How CBGB’s became more punk and more male-dominated and hardcore, and became less sort of friendly to people that were more divergent. And by that time, I had already kind of moved on and was finishing school and looking for a job and stuff like that. But, I just don't remember it ever being like that when I was there, so things keep changing.

AV: For sure. Well, I wanted to talk to you about your images because some of them— I mean, they're very, very striking— and you had some great people to work with that were stylized just on their own. Whether it's James Chance, Anya, or I think about people like Arto Lindsay and his sort of bespectacled self….Ikue Mori. But you had some great subject matter to work with, shooting black and white, these very stark sort of contrasts, and I was wondering just about your approach coming from design and how you figured out your own style as a photographer.

Julia Gorton: You know, I can think about why the work looks the way it does, I don't think I was aware that my work was looking a particular way that kind of framed it at the time. I can look at it now and people will say to me, your work actually has created the image of what that time was like. And I think, ‘that’s not the whole story.’ It's like just one photographer's slice of this. And so if you look at David Godlis’s work— same band, same people. You can't say like, ‘this is everything that's there.’ We were all next to each other, doing things that were slightly different. And I think, for example, he always talks about how he was inspired by street photography and documentary photography and Brassaï. And I didn't know who Brassaï was. So I was more inspired by, when I sort of investigate what I can remember of my past and what I was seeing, I remember looking at a William Klein book I really liked in the library, and when I looked at it recently I'm like, ‘oh yeah, it's really contrasty and it's kind of gritty and it's like up in your face.’ I loved fashion photography and I liked horror films, so it was like these things, you put them in a blender. It's like, here's a little bit of horror, here's a little bit of fashion, here's a little bit of movie, and then here's a little bit of just like something weird. I just think the way things come out, they come out because of what you know and what you don't know. The building blocks and then this sort of refraction through yourself of the new in some ways.

AV: Well, I wanna talk to you about your book. This is really exciting. You have this new book coming out called Nowhere New York: Dark, Insulting and Unmelodic, which I find to be very telling…

Julia Gorton: That came out of Phil Dray’s essay. I read it and I thought, this is so funny, maybe it could be like the subhead for this. And so he said it was fine, but I thought for a long time about what to call it. And originally it was called Feels So Good because it was off of a George Scott— I think it was a Chick Corea— shirt he's wearing or something like that. And I thought, his expression and that slogan, I thought it just feels so not right.

AV: Like a tension with the irony a little bit?

Julia Gorton: Yeah, so I moved away from it finally when— I don't even know where this came, like how the name came about— but it felt like the right name for the book.

(DNA backstage at Max’s Kansas City, 1978. Photo by Julia Gorton.)

AV: Well, it's got wonderful photographs from your time with Beat It! and doing stuff for New York Rocker. There’s also some great essays from people who were around the scene, people like Thurston Moore, and Lydia does the introduction to it. In looking back on it and seeing it all come together like that, what's it been like for you to put a project like this out and to assemble it?

Julia Gorton: Well, it'll be interesting to see how people respond to it because the book’s gone through a lot of different changes and the people I showed it to over the time it was in development, like different friends or colleagues or contacts said, “Oh, it needs more bands. It needs more about the music.” I’m like, okay, I'll put that in. And then it's like, “Oh, it needs more about the venues.” I'm like, okay, I'll put that in. It's like, “Oh, it needs more about the personalities and people in the clubs.” I'm like, okay, I'm trying to get it built out. “Oh, it's gotta be about you.” I'm like, okay, it’s about me. “Oh, it's gotta be about the scene. Don't you have more ephemera?” I'm like, okay, okay. You know? So all those things came together and at that time I started asking people to write for me. It’s like, “Could you write something about photography in New York? Or just really, really vague, like when you came to New York or DJing.” And so, although the essays are copy-edited, they came in pretty much like personal remembrances, mostly. And so I feel like the book functions almost like a collaborative, crowdsourced memoir of the scene. So, it's my book, my photos and my shaping of it, but without those voices it wouldn't be as interesting and personal and complex. So I feel really grateful that Lucy Sante wrote an amazing, amazing essay where you're reading it and you're like, ’Is that what happened? Is that what I did? Is that who I am? Oh my god…’ It gives you a perspective for where you might have fit then. But there are lots of voices that don't have that kind of name recognition, and I've always felt that they were as important as the images and as the text to include.

AV: I actually wanted to ask you about that, because I think not only in the essays that are presented, you get this insider's perspective from all these different viewpoints and vantage points. Which is fascinating to look at it through the different people's eyes, even your own, and talk about New York and the way you're viewing it, versus the way it's been sort of depicted in the No Wave historical retrofitting that's gone on a little bit. But also, a lot of people that you've photographed in there are not gonna be household names, even within the sort of No Wave iconography.

Julia Gorton: You know, I think people have to do their research. To me they are household names. It's interesting how people respond to the images, because this picture here of Willie Klein, that's in that collage [points to picture], he was included in Thurston and Byron's book. And people responded really strongly to that just because of the feeling you get of him as a person. And he's quite direct and sexy and appealing. And it didn't matter that he's not like the biggest name out there in the world. He still has a star kind of quality, and for me everybody is a star on this stage, you know? It's like, we went out there and we did it and people should know who they are. And if you don't and you don't get out and research, it's your fault, you know?

AV: Well, it's a fascinating look at that time period and can’t wait for people to check it out. But you've had a very interesting creative career overall, since starting out doing this photography and capturing all these wonderful images from these scenes from CBGB and the No Wave stuff onward, then working with National Lampoon and Condé Nast, and then being an illustrator for children's books. Which is kind of a far stretch from Lydia Lunch.

Julia Gorton: Somebody DM’d me on Instagram and they're like, “Just wanted to ask you a question, did you do children's books?” I'm like, “Yeah, I did.” [laughs] I worked at New York Rocker. I knew Laura Levine, who's an amazing photographer. Laura had a friend, Arlene. Arlene was working at National Lampoon and they needed somebody. So I was graduating, and I went and interviewed and I got a job at this big national magazine that was like, ‘we read this in high school, like, oh my god, I can actually walk in there?’ It was a really interesting place. I met my husband there. He was an illustrator coming in and when I describe myself back then, I think I was always sort of like ‘What? He painted that? What? They cut their hair like that? Like, oh my god, there's an elevator in that building?’ Everything seemed kind of like, ‘Wow! You can do that? Aren't there rules against that?’ Anyways, so yeah, I worked there and then I went and I worked at— I worked twice at Condé Nast. The first time I got politely fired in a sort of underhanded way, but I hated it there. And then they hired me back freelance and treated me like a queen. So, these places were very different from each other. I also worked at a housewares magazine for Fairchild. And I did some magazine startup stuff. So, it wasn't like New York Rocker and it wasn't really the right fit for me. And so at a certain point, my husband and I had a child and I was like, how can I work at home? And I started doing illustration work and it worked for a long time. And I made a lot of paintings— like thousand of paintings, easily. But I'm done with that.

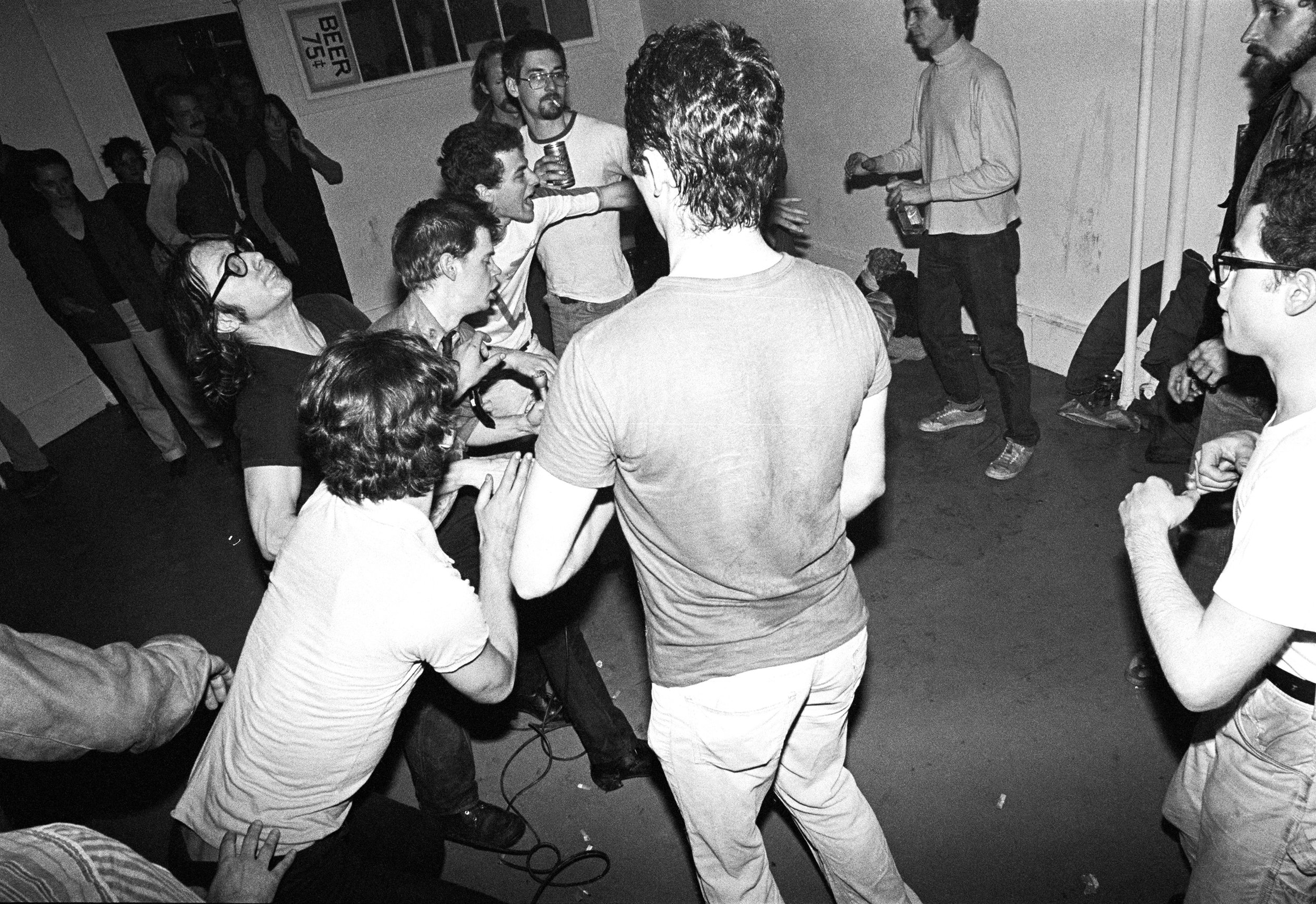

AV: Quite the career arc from photographing James Chance attacking Robert Christgau.

Julia Gorton: What's funny is, my memory of that is he had insulted Christgau’s wife and Christgau was having nothing to do with it, but then I bet there was some other version of that story. And so, yeah, everybody remembers things a little differently. And if you go through my book, one person will say like, “Oh, this term, No Wave came from this place.” And that person will say, “Oh, this term, No Wave came from this person.” And that person will say like, “Oh, I think so-and-so coined that term.” So, I like that within the book there are some stories that are told from different parties in action, and they contradict each other. Depending on who the narrator is you get a different story.

AV: A different building block as it were.

Julia Gorton: Yeah.

(James Chance attacks music critic Robert Christgau at Artist’s Space, 1978. Photo by Julia Gorton.)

AV: I wanted to ask you, I know since working with National Lampoon and Condé Nast you did work at Parsons teaching design, and just wanted to know what you're doing now— and next— and what people can maybe expect from you in the future. After this book comes out, are there other projects you're looking forward to?

Julia Gorton: I taught at Parsons for a long time and I was the program director. So, I might be happy that I'm not teaching there anymore, but I think there were things I learned teaching there and working there that were really beneficial in getting my book together, doing what I did today with these kind of messy, loose, open engagements with the community [the day of the interview she had been doing open portrait sessions at the 309 Punk Project house]. And so, a part of me is like, these things create anxiety for me in a way, but they're also enjoyable because you meet people and you sort of stretch your skills a little bit. So, this time period post-COVID— or COVID time period— kind of slowed everything down a lot. And I was focused on finishing my book. And so, my wishes are sort of immediate: finish the book, get the book into the garage— because I'm self-publishing it— sell the book. Pretty simple. Complete that, move on. So, do I want to do another book like this? Not at this minute. No, I never wanna do another book. They are way more work than you can imagine. But that might change in a year, so I'm not really sure.

AV: Will we see you back in Pensacola at some point?

Julia Gorton: Oh, I hope so, yeah. I mean, the community here is like really top-notch and super friendly and cool. And you know, it's a good, good bunch of people. I'm like, how did I get so lucky that I got to come down here? How did Felicia find me? And then think that I should come be in this show? And I feel so incredibly grateful that people do reach out because that's really what it's all about is that connecting and doing stuff. So, at this time— I pretty much photographed anybody back in the day, I photographed anybody I wanted to do. So if I asked someone if I could photograph them, I don't remember anybody ever saying no. So, you know, when I went to do my book and I asked people to write essays for me, nobody said no. And so I thought, ‘my god, I love this.’ People are so nice. And we need that help of everybody to get things done. It's a lot of heavy lifting.

AV: There's an intimacy and an immediacy to the pictures that you could tell you had the trust of the people you were working with, and I think that really comes through. I think that's a very important part of why you were able to capture so many of these amazing images.

Julia Gorton: Yeah, I think people saw my work at the time, like in New York Rocker or around. So I think some people might have had a little bit of an idea of who I was, but I pretty much was under the radar. It was like a little tiny, tiny scene. So it's always nice to hear and to see that people are still out there doing stuff. And that Rick’s band is successful and people like his music. I think that's amazing that after all these years he could still be doing— we could still be doing— some variation of this, for sure.

AV: It’s amazing. Thanks so much for your time!